Pearl Harbor

From the Quicksilver Metaweb.

This is a page for Pearl Harbor

Stephensonia

Lawrence Waterhouse survives the day of infamy. It is the start of his new career in code cracking.

Authored entries

- TBA - this will be made one

Community entry: Pearl Harbor

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia.

Aerial view of Pearl Harbor, Ford Island in center.

Arizona memorial is the small white blob just

below island, on the right side.

Pearl Harbor is a US Navy deep water naval base, headquarters of the Pacific Fleet on the island of O'ahu, Hawai'i, near Honolulu.

History of Pearl Harbor before 1941

Originally an extensive, shallow inlet or bay called Wai Momi, meaning "Water of Pearl", or Pu'uloa, by the Hawaiians, Pearl Harbor was regarded as the home of the shark goddess Ka'ahupahau and her brother Kahi'uka. The harbor was teeming with pearl-producing oysters until the late 1800's. In the early days following the arrival of Captain James Cook, Pearl Harbor was not considered a suitable port due to the shallow water.

The United States of America and the Hawaiian Kingdom signed the Reciprocity Treaty of 1875 as Supplemented by Convention on December 6, 1884 and ratified in 1887. On January 20, 1887, the United States Senate allowed the Navy to lease Pearl Harbor as a naval base (the US took possession on November 9 that year). As a result, Hawai'i obtained exclusive rights to allow Hawaiian sugar to enter the United States duty free. The Spanish-American War of 1898 and the need for the United States to have a permanent presence in the Pacific both contributed to the decision to annex Hawaii.

After annexation, Pearl Harbor was refitted to allow for more navy ships. Schofield Barracks, constructed in 1909 to house artillery, cavalry and infantry units, became the largest Army post of its day.

In 1917 Ford Island in the middle of Pearl Harbor was purchased for joint Army and Navy use in the development of military aviation. As Japanese presence increased in the Pacific, the US increased the ships' presence there.

Satellite image of Pearl Harbor

With tensions rising between the United States and Japan in 1940, the US began training operations at the base. Pearl Harbor was the site of a surprise attack on the United States by Japanese military forces on Dec. 7, 1941. Japanese ships and airplanes attacked the United States naval base at Pearl Harbor on the island of Oahu in Hawaii. The attack caused heavy casualties and destroyed much of the American Pacific Fleet. The attack also brought the United States into World War II. "Remember Pearl Harbor" became the rallying cry for the country. American participation was a crucial reason why the embattled Allied nations, including the United Kingdom (U.K.) and Soviet Union, turned the tide and defeated the Axis nations, headed by Japan and Germany.

Background

Japan began a military expansion during the 1930's. It invaded China and much of Southeast Asia. Japan wanted to acquire the rich resources of Asia. The United States protested this aggression. It demanded that Japan stop its actions, but Japan ignored the demand. The United States then cut off exports to Japan. Japan had few natural resources, and it relied on exports of petroleum and other goods from the United States.

General Hideki Tojo became premier of Japan in October 1941. Tojo and other Japanese military leaders realized that only the United States Navy had the power to block Japan's expansion in Asia. They decided to try to cripple the U.S. Pacific Fleet at anchor in Pearl Harbor.

Attack on Pearl Harbor

On the morning of December 7, 1941, planes of the Imperial Japanese Navy carried out a surprise assault on the American Navy base and Army air field at Pearl Harbor, Oahu, Hawaii Territory, now Hawaii. This attack has been called the Bombing of Pearl Harbor and the Battle of Pearl Harbor but, most commonly, the Attack on Pearl Harbor or simply Pearl Harbor.

The Japanese planes bombed all the US military air bases on the island (the biggest was the U.S. Army air base at Hickam Field), and the ships anchored at Pearl, including "Battleship Row". The battleship USS Arizona blew up, turned over, and sank with a loss of over 1,100 men, nearly half of the American dead. It became and remains a memorial to those lost that day. Seven other battleships and twelve other ships were sunk or damaged, 188 aircraft were destroyed, and 2,403 Americans lost their lives.

On November 26 a fleet of six aircraft carriers commanded by Japanese Vice Admiral Chuichi Nagumo left Bay Hitokapu Bay headed for Pearl Harbor under strict radio silence.

The Japanese aircraft carriers were: Akagi, Hiryu, Kaga, Shokaku, Soryu, Zuikaku. Together they had a total of 441 planes, including fighters, torpedo-bombers, dive-bombers, and fighter-bombers. The planes attacked in two waves, and Admiral Nagumo decided to forego a third attack in favor of withdrawing. Of these, 55 were lost during the battle.

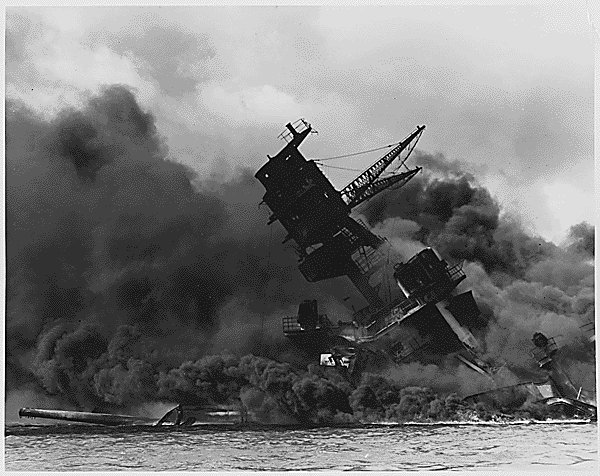

The USS Arizona burning after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor

Strategy

The purpose of the attack on Pearl Harbor was to neutralize American naval power in the Pacific, if only temporarily. Yamamoto himself suggested that even a successful attack would gain only a year or so of freedom of action. Japan had been embroiled in a war with China for some years (starting in 1931) and had seized Manchuria some years before. Planning began for a Pearl Harbor attack in support of further military advances in January of 1941, and training for the mission was underway by mid-year when the project was finally judged worthwhile after some Imperial Navy infighting.

Background

The Japanese move into southern Indo-China, beginning in mid-1941, provoked the major powers in the area into action, more than the diplomatic protest notes which had been the usual for nearly a decade: the United States, with Britain and the Dutch colonial government, imposed an embargo on strategic materials to Japan in July. This "threat" to the Japanese economy (and to the military's supplies) was intended to force a reconsideration of the move into Indo-China and perhaps even to the negotiating table. Roosevelt's decision to leave the Fleet in Pearl (closer to Japan than the US West coast, and so an increase in 'threat') is said to have been part of this response. The US, and other Powers, reaction seems instead to have increased the Japanese military's commitment to a conquer and exploit approach against areas holding the resources endangered by the new embargo. With very limited oil production and minimal refined fuel reserves, Japan faced a real, and serious, problem. The Japanese leadership took the embargo as the stimulus to activate plans to seize supplies of strategic material in Asia, particularly southeast Asia. They could not expect the United States to remain passive when those plans were activated; it was this which had already led Admiral Yamamoto to consider ways to pre-emptively neutralize American power in the Pacific.

His idea of an attack on the naval base at Pearl Harbor was one tactic to achieve this strategic goal. Japanese sources indicate that Yamamoto began to think about a possible strike at Pearl very early in 1941, and that, after some preliminary studies, had managed to start preliminary operational planning for it some months later. There was substantial opposition to any such operation within the Japanese Navy, and at one point Yamamoto threatened to resign if the operational planning were stopped. Permission to set up the operation was given in late summer at an Imperial Conference attended by the Emperor, and permission to actually stage the force into the Pacific in preparation for the attack was given at another Imperial Conference, also attended by the Emperor, in November.

Immediate outcome

In terms of its strategic objectives the attack on Pearl Harbor was, in the short to medium term, a spectacular success which eclipsed the wildest dreams of its planners and has few parallels in the military history of any era. For the next six months, the United States Navy was unable to play any significant role in the Pacific War. With the U.S. Pacific Fleet essentially out of the picture, Japan was free of worries about the other major Pacific naval power. It went on to conquer southeast Asia, the entire southwest Pacific and to extend its reach far into the Indian Ocean.

Longer-term effects

In the longer term, however, the Pearl Harbor attack was an unmitigated strategic disaster for Japan. Indeed Admiral Yamamoto Isoroku, whose idea the Pearl Harbor attack was, had predicted that even a successful attack on the U.S. Fleet would not and could not win a war with the US, as American productive capacity was too large. One of the main Japanese objectives was the three American aircraft carriers stationed in the Pacific, but these had sortied from Pearl Harbor a few days before the attack and escaped unharmed. Putting most of the U.S. battleships out of commission, was widely regarded -- in both Navies and in most observers worldwide -- as a tremendous success for the Japanese. The elimination of the battleships left the U.S. Navy with no choice but to put its faith in aircraft carriers and submarines, these being most of what was left -- and these were the tools with which the U.S. Navy halted and then reversed the Japanese advance. The loss of the battleships didn't turn out to be as important as most everyone thought before (in Japan) and just after (in Japan and the U.S.) the attack.

Probably most significantly, the Pearl Harbor attack immediately galvanized a divided nation into action as little else could have done. Overnight, it united the US with the goal of fighting and winning the war with Japan, and it probably made possible the unconditional surrender position taken by the Allied Powers. Some historians believe that Japan was doomed to defeat by the attack on Pearl Harbor itself, regardless of whether the fuel depots and machine shops were destroyed or if the carriers had been in port and sunk.

U.S. response

On December 8, 1941, the U.S. Congress declared war on Japan with only one dissenting vote. Franklin D. Roosevelt both proposed and signed the declaration of war shortly afterward, calling the previous day "a date which will live in infamy." The U.S. Government continued and intensified its military mobilization, and started to convert to a war economy.

A related, and still unanswered, question is why Nazi Germany declared war on the United States December 11, 1941 immediately following the Japanese attack. Hitler was under no obligation to do so under the terms of the Axis Pact, but did anyway. This doubly outraged the American public and allowed the United States to greatly step up its support of the United Kingdom, which delayed for some time a full U.S. response to the setback in the Pacific.

Historical significance

This battle, like the Battle of Lexington and Concord, had history-altering consequences. It only had a small military impact due to the failure of the Japanese Navy to sink U.S. aircraft carriers, but it firmly drew the United States into World War II leading to the defeat of the Axis powers worldwide. The Allied victory in this war and US emergence as a dominant world power has shaped international politics ever since.

Aftermath

Despite the perception of this battle as a devastating blow to America, only five ships were permanently lost to the Navy. These were the battleships USS Arizona, USS Oklahoma, the old target ship USS Utah, and the destroyers USS Cassin and USS Downes; nevertheless, much usable material was salvaged from them, including the two aft main turrets from the Arizona. Four ships sunk during the attack were later raised and returned to duty, including the battleships USS California, USS West Virginia and USS Nevada. Of the 22 Japanese ships that took part in the attack, only one survived the war.

The USS Utah Capsizing During

The Attack On Pearl Harbor

Public domain photo from the NHC

There are many who say that the Japanese would have been wise to have attacked with a third strike to destroy the oil storage facilities, machine shops and dry docks at Pearl Harbor. Destruction of these facilities would have greatly increased the U.S. Navy's difficulties as the nearest Fleet facilities would have been several thousand miles east of Hawaii on the West Coast of the States. Admiral Nagumo declined to order a third strike for several reasons. * First, losses during the second strike had been more significant than during the first, a third strike could have been expected to suffer still worse losses. * Second, the first two strikes had essentially used all the previously prepped aircraft available, so a third strike would have taken some time to prepare, allowing the Americans time to, perhaps, find and attack Nagumo's force. The location of the American carriers was and remained unknown to Nagumo. * Third, the Japanese planes had not practiced attack against the Pearl Harbor shore facilities and organizing such an attack would have taken still more time, though several of the strike leaders urged a third strike anyway. * Fourth, the fuel situation did not permit remaining on station north of Pearl Harbor much longer. The Japanese were acting at the limit of their logistical ability to support the strike on Pearl Harbor. To remain in those waters for much longer would have risked running unacceptably low on fuel. * Fifth, the timing of a third strike would have been such that aircraft would probably have returned to their carriers after dark. Night operations from aircraft carriers were in their infancy in 1941, and neither the Japanese nor anyone else had developed reliable technique and doctrine. * Sixth, the second strike had essentially completed the entire mission, neutralization of the American Pacific Fleet. * Finally, there was the simple danger of remaining near one place for too long. The Japanese were very fortunate to have escaped detection during their voyage from the Inland Sea to Hawaii. The longer they remained off Hawaii, they more danger they were in, e.g., from a lucky U.S. Navy submarine, or from the absent American carriers.

Despite the debacle, there were American military personnel who served with distinction in the incident. An ensign got his ship underway during the attack. Probably the most famous is Doris Miller, an African-American sailor who went beyond the call of duty during the attack when he took control of an unattended machine gun and used it in defense of the base. He was awarded the Navy Cross.

The attack has been depicted, more (or less) accurately, numerous times on film. Examples include: * From Here to Eternity * Tora! Tora! Tora! * Pearl Harbor

The surprise attack on Pearl Harbor and the resulting state of war between Japan and the United States were factors in the later Japanese internment in the western United States. Another important factor were the racial views of General John DeWitt, commander of the West Coast Defense District. He claimed existence of evidence of sabotage and espionage intentions among the Japanese and Japanese descended in support of his recommendation to President Roosevelt that those of Japanese descent be interned. He had no such evidence.

In 1991, it was rumored that Japan was going to release an official apology to the United States for the attack. The apology did not come in the form many expected, however. The Japanese Foreign Ministry released a statement that said Japan had intended to release a formal declaration of war to the U.S. at 1 P.M., twenty-five minutes before the attacks at Pearl Harbor were scheduled to begin. However, due to various delays, the Japanese ambassador was unable to release the declaration until well after the attacks had begun. For this, the Japanese government apologized.

Advance Knowledge Debate

There has been considerable debate ever since December 8, 1941, as to how and why the United States had been caught unaware, and how much and when American officials knew of Japanese plans and related topics. Some have argued that various parties (in some theories Roosevelt and/or other American officials, or Churchill and the British, in others all of the above, or additional players) knew of the attack in advance and may even have let it happen, or encouraged it, in order to force America into war.

Examination of information released since the War has revealed that there was considerable intelligence information available to US, and other, officials. It was the failure to process and use this information effectively that has led some to invoke conspiracy theories rather than a less interesting mix of mistake and incompetence. The US government had six official enquires into the attack - The Roberts Commission (1941), the Hart Inquiry (1944), the Army Pearl Harbor Board (1944), the Naval Court of Inquiry (1944), the Congressional Inquiry (1945 - 1946) and the top-secret inquiry by Secretary Stimson authorized by Congress and carried out by Henry Clausen (the Clausen Inquiry (1945)).

One factor making an attack against Pearl Harbor 'unthinkable' was the shallow anchorage at Pearl Harbour. Such depths were generally considered to make effective torpedo attack impossible; at the time, torpedoes dropped from planes went deep before attaining running depth and in too shallow water (like Pearl Harbor) would hit the bottom, exploding prematurely, or just digging into the mud. But the British had proved that modified torpedoes could manage in shallow water during their attack on the Italian Navy at Taranto on November 11, 1940. The US Navy overlooked the significance of this new development. The Japanese had independently developed shallow water torpedo modifications during the planning and training for the raid in 1941.

US signals intelligence in 1941 was both impressively advanced and uneven. The US MI8 operation in New York had been shut-down by Henry Stimson (Hoover's newly appointed Secretary of State), which provoked its director, Herbert Yardley to write a book (The American Black Chamber) about its successes in breaking other nation's crypto traffic. Most responded promptly by changing (and generally improving) their cyphers and codes, forcing other nations to start over in reading their signals. The Japanese were no exception. Nevertheless, US cryptanalytic work continued after Simson's action in two separate efforts by the Army's Signal Intelligence Service (SIS) and the Office of Naval Intelligence's (ONI) crypto group, OP-20-G. The US was able, in the period just before December 1941, to read several Japanese codes and ciphers. By 1941, those groups had broken several Japanese cyphers (mostly diplomatic ones, eg 'PA-K2' and the 'Purple Code') and had made some progress against some naval codes/cyphers (eg, the pre-December version of JN-25). In fact, the break of the Purple cypher was a considerable cryptographic triumph and proved quite useful later in the War. It was the highest security Japanese Foreign Office cypher, but prior to Pearl Harbor carried little information about future events planned by the Japanese; the military, who were essentially determining policy for Japan, didn't trust the Foreign Office and left them 'out of the loop'. Unfortunately, the two US groups generally competed rather than cooperated, and distribution of intelligence from the military to US civilian policy-level officials was poorly done, and furthermore done in a way that prevented any of its recipients from developing a 'larger sense' of the meaning of the decrypts.

Japanese intelligence efforts against Pearl Harbor included at least two German Abwehr agents, one of them a sleeper living in Hawaii with his family; he and they were essentially incompetent. The other, Dusko Popov a Yugoslavian businessman, was quite effective in Abwehr eyes, but unknown to them was a double agent whose loyalty was to the British. He worked for the XX Committee of MI5. In August 1941 he was tasked by the Abwehr with some specific questions about Pearl (see John Masterman's book on the Double Cross operation for the text of the questionnaire), but the FBI seems to have evaluated the effort as of negligible importance. There has been no report that its existence, or Popov's availability as a double agent, was even passed on to US military intelligence or to civilian policy officials. J. Edgar Hoover dismissed Popov's importance noting that his British codename, Tricyle, was connected with his sexual tastes. (Strike while the irony is hot!) In any case, he was not allowed to continue on to Hawaii and to develop more intelligence for the UK and US.

Throughout 1941, the US, Britain, and Holland collected a considerable range of evidence suggesting that Japan was heading for war against someone new. But the Japanese attack on the US in December was essentially a side operation to the main Japanese thrust south against Malaya and the Phillipines -- many more resources, especially Imperial Army resources, were devoted to these attacks as compared to Pearl. Many in the Japanese military (both Army and Navy) had disagreed with Yamamoto's idea of attacking the US Fleet at Pearl Harbor when it was first proposed to them in early 1941, and remained reluctant through the Imperial Conferences in September and November which first approved it as policy and then authorized the attack. The Japanese focus on South-East Asia was quite accurately reflected in US intelligence assessments; there were warnings of attacks against Thailand (the Kra Peninsula), against Malaya, against French Indochina, against the Dutch East Indies, even one against Russia. There are reports of concern in the Pentagon and the White House about Japanese plans for the region. But, there had already been a specific claim of a plan for an attack on Pearl Harbor from the Peruvian Ambassador to Japan in early 1941. Since not even Yamamoto had yet then even decided to argue for an attack Pearl Harbor, discounting US Ambassador Grew's report to Washington about it, in early 1941, was quite sensible. There has been no report of a serious prior conviction by anyone in US or UK military intelligence or among US civilian policy officials that Pearl Harbor or the US West Coast would be attacked. The so-called "Winds Code" announcing the direction of new hostilities remains a curious and confused episode, demonstrating the uncertainty of meaning inherent in most intelligence information, and in this case, even uncertainty about the existence of some intelligence information, especially some years after the event.

Nevertheless, in late November, both the US Navy and Army sent explicit war warnings to all Pacific commands. Uniquely among those Pacific commands, the local Hawaii commanders, Admiral Kimmel and General Short did little to prepare for war, including an attack on their forces, in their command areas. Inter-service rivalries between Kimmel and Short did not improve the situation.

As Nagumo's attacking force neared Hawaii, there is claimed by some to have been a flurry of later warnings to US intellegence and, even, directly to the White House. For instance, the SS Lurline, heading from San Francisco to Hawaii on its regular route, is said to have heard and plotted unusual radio traffic. That traffic is further said to have been from the Japanese fleet. There are problems with this. All surviving officers from Nagumo's ships claim that there was no radio traffic to have been overheard; their radio operators had been left in Japan to fake traffic for the benefit of listeners (ie, military intelligence in other countries), and all radios aboard Nagumo's ships were claimed to have been physically locked to prevent inadvertent use and thus remote tracking of the attack force. Unfortunately, the Lurline's log (seized by either Navy or Coast Guard officers in Hawaii after arrival) hasn't been found, so contemporaneous evidence of what was recorded about what was heard isn't available. ONI is further said to have been aware of the eastwards movement of Japanese carriers from other sources, but nothing in the way of compelling evidence on this point has yet turned up. There remains controversy on these points.

Closer to the moment of the attack, the attacking planes were detected and tracked in Hawaii by an Army radar installation being used for training, mini-subs were sighted and attacked ourside Pearl Harbor and at least one was sunk -- all before the planes came within bombing range.

Japanese consular officials in Hawaii, including spy and Naval officer Takeo Yoshikawa, had been sending information to Tokyo about conditions in Hawaii, and in Pearl Harbor, for some months. Some of this information was hand delivered to intelligence officers aboard Japanese vessels calling in Hawaii, but some was transmitted back to Tokyo. Many of the messages in this last group were overheard and decrypted; most were evaluated as the sort of intelligence gathering all nations routinely do about potential opponents. None of those known, including those decrypted later in the War when there was time to return to them, explicitly stated anything about an attack on Pearl; the only exception was a message sent on 6 December, which was not decrypted until after the 7th and which thus became moot. No cable traffic (the usual communication method to/from Tokyo) was intercepted in Hawaii until after David Sarnoff of RCA agreed to assist in a visit to Hawaii immediately before the 7th; such interception was illegal under US law. Locally, Naval Intelligence in Hawaii had been tapping telephones at the Japanese Consulate before the 7th, and overheard a most peculiar discussion of flowers in a call to Tokyo (the significance of which is still opaque and which was discounted in Hawaii at the time), but the Navy's tap was discovered and was disconnected by the Navy in the first week of December. They didn't tell the local FBI about either the tap or its removal; the local FBI agent in charge later claimed he would have had installed one of his own if he'd known the Navy's had been disconnected.

Further reading

- The monumental trilogy by Gordon W. Prange and his collaborators Donald M. Goldstein and Katherine V. Dillon, At Dawn We Slept (McGraw-Hill, 1981), Pearl Harbor: The Verdict of History (McGraw-Hill, 1986), and December 7, 1941: The Day the Japanese Attacked Pearl Harbor (McGraw-Hill, 1988), is considered the standard work.

- Walter Lord, Day of Infamy (Henry Holt, 1957) is a very readable, and entirely anecdotal, re-telling of the day's events.

- W. J. Holmes, Double-Edged Secrets: U.S. Naval Intelligence Operations in the Pacific During World War II (Naval Institute, 1979) contains some important material, such as Holmes' point that had the U.S. Navy been warned of the attack and put to sea, it would have likely resulted in an even greater disaster, as all the ships sunk would have been lost completely in deep water anchorages, along with a higher loss of life. Holmes was one of the cryptographers stationed in Hawaii.

- Michael V. Gannon, Pearl Harbor Betrayed (Henry Holt, 2001) is a recent examination of the issues surrounding the surprise of the attack.

- Frederick D. Parker, Pearl Harbor Revisited: United States Navy Communications Intelligence 1924-1941 (Center for Cryptologic History, 1994) contains a quite detailed description of what the Navy knew from intercepted and decrypted Japanese communications prior to Pearl.

- Henry C. Clausen and Bruce Lee, Pearl Harbor: Final Judgement, (HarperCollins, 2001), is an account by Henry Clausen himself of the secret Clausen Inquiry undertaken late in the War by order of Congress to Secretary of War Stimson. Clausen's effort was extraordinary, if only because of the exploding vest he wore as he traveled, and the astonishing letter of authority Stimson gave him. His account supports the 'bumbling around in Washington' and the 'bumbling around in Hawaii' theories, but not the 'Roosevelt knew and invited the Japanese in' variant. He also thinks that Kimmel and Short both failed in their duty to be as prepared as they could with the resources they had. He also faults General Marshall for committing perjury (!). Clausen admired MacArthur despite the losses in MacArthur's area of responsibility (the Philipines); in part it seems because they were both committed Masons. Of course, Clausen's invetigative brief did not include being caught by surprise in the Philipines and the resulting losses there. It's worth reading.

Further reading - Alternative Theories

- John Toland, Infamy: Pearl Harbor and Its Aftermath (Berkeley, reissue edition 1991) is an account of the various investigations of the US failure to be prepared at Pearl. He claims that Roosevelt had advance knowledge of the attack, which he deliberately did not use to warn the commanders at Pearl. Note that some of Toland's sources have since said that his interpretation of their experiences is incorrect.

- James Rusbridger and Eric Nave, Betrayal at Pearl Harbour: How Churchill Lured Roosevelt into WWII (Summit, 1991) which posits that while the Americans couldn't read the Japanese naval code (JN-25), the British could, and Churchill deliberately withheld warning because the UK needed U.S. help. Nave was an Australian cryptographer whose diaries were used in writing this book. A check against them has made clear that some of the charges Rusbridger makes here are unsupported by Nave's diaries of the time.

- Robert Stinnett, Day Of Deceit: The Truth About FDR and Pearl Harbor (Free Press, 2001) is a recent examination which begins with the conviction that Roosevelt deliberately steered Japan into war with America, and ends with the same conclusion. Stinnett's understanding of cryptography/cryptanalysis is quite limited and his conclusions regarding the cryptographic evidence are accordingly unreliable. He also sees a great deal of meaning in short analysis memos which support his thesis and less meaning in other information that does not. A distinctly limited account, though including an impressive research record.

Further reading - Some Reminiscences

- Robert A. Theobald, Final Secret of Pearl Harbor (Devin-Adair Pub, 1954) ISBN 0815955030 ISBN 0317659286 Foreword by Fleet Admiral William Frederick Halsey, Jr.

- Albert Coady Wedemeyer|Albert C. Wedemeyer, Wedemeyer Reports! (Henry Holt Co, 1958) ISBN 0892750111 ISBN 0815972164

- Hamilton Fish, Tragic Deception: FDR and America's Involvement in World War II (Devin-Adair Pub, 1983) ISBN 0815969171

External Links

- "Pearl Harbor Attacked" Message Board — A wonderful site with lots of personal recollections, etc - see particularly the two "Intelligence" boards, which have a host of useful articles posted

- Naval Institute Special Collections: Pearl Harbor — Articles, books, and pictures

Alternative Theories

- Did Roosevelt know in advance about the attack on Pearl Harbor yet say nothing? — The Straight Dope, Straight Dope Science Advisory Board, February 28, 2001

- The Independent Institute: Pearl Harbor Archive — Mostly a Stinnett site, but also has Pearl Harbor articles, debates, interviews, transcripts, book reviews, books, and Pearl Harbor documents

- Communism at Pearl Harbor — An article proposing that the Russians maneuvered the U.S. into war

War memorials

The ships destroyed in the Pearl Harbor attack include the U.S.S. Arizona. The battleship sits upright on the bottom of the harbor with more than 1,000 men entombed aboard. The U.S.S. Arizona Memorial, a roomlike structure, stands above the ship. The memorial is supported by pilings that reach the harbor bottom. About 1 1/2 million people visit the memorial each year. The names of those who died on the Arizona are carved in marble at one end of the room. Even today, bubbles of oil from the sunken Arizona rise to the water's surface. In 1999, the U.S. battleship Missouri was opened to the public, as the Battleship Missouri Memorial, in Pearl Harbor near the Arizona. This ship was the one on which the Japanese surrendered to the Allies, on Sept. 2, 1945.

Pearl Harbor Naval Complex

Pearl Harbor is now the site of the Pearl Harbor Naval Complex. It covers about 12,600 acres (5,100 hectares) on Oahu Island. Five major fleet commands in the Pacific have headquarters at the base.