Robert Hooke

From the Quicksilver Metaweb.

This is an intermediate page for Robert Hooke.

Big Science News

Robert Hooke: the man who knew everything

Stephensonia

Hooke is almost a match for the more politically savvy Isaac.

Authored entries

- Boyle's law

- Hooke's Law

- Hooke's Law (Professorbikeybike)

- Boyle's Law, aka Hooke's, Boyle's, and Mariotte's Law (Neal Stephenson)

- Stephenson:Neal:Quicksilver:37:...less fraught with seasickness, pirates, scurvy, mass drownings... (Alan Sinder)

- Stephenson:Neal:Quicksilver:78:Isaac Barrow (Neal Stephenson)

- Stephenson:Neal:Quicksilver:112:at Epsom (Neal Stephenson)

- Stephenson:Neal:Quicksilver:114:Hooke approaches (Neal Stephenson)

- Stephenson:Neal:Quicksilver:128:Fly stuck to quill (Neal Stephenson)

Community entry: Robert Hooke

Robert Hooke (July 18, 1635 - March 3, 1703) was one of the greatest experimental scientists of the seventeenth century, and hence one of the key figures in the Scientific revolution.

Robert Hooke

Based on the Recently Found

Royal Society Portrait

A True Science Hero

Born in Freshwater, on the Isle of Wight, Hooke received his early education at Westminster School. In 1653, Hooke won a place at Oxford. There, he met Robert Boyle, and was employed as his assistant. In 1660, he discovered Hooke's Law of elasticity, which describes the linear variation of tension with extension in an elastic spring. In 1662, Hooke was appointed Curator of Experiments to the newly founded Royal Society, and was responsible for experiments performed at its meetings. In 1665, he published a book entitled Micrographia, which contained a number of microscopic and telescopic observations, and some original biology. Indeed, the biological term cell is attributed to Hooke. Also in 1665, he was appointed Professor of Geometry at Gresham College.

Robert Hooke also achieved fame as the chief assistant of Christopher Wren helping to rebuild after the Great Fire of London in 1666. He worked on the Royal Greenwich Observatory, and the infamous Bethlehem Hospital, Bedlam. He died in London.

Micrographia

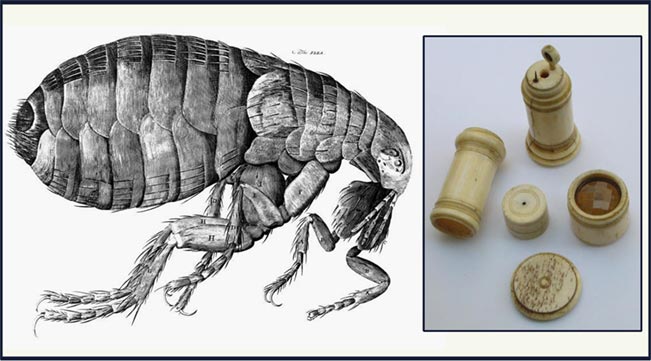

The other importance of Micrographia is that it is the first scientific text published in English and not Latin. The image below is a photo of the flea seen in Quicksilver and a replica of the compound microscope Hooke used to observe the specimens illustrated in Micrographia. There is a lens at either end of the instrument and a third inside the barrel. The bone flea-glass telescope performs both as a telescope and a microscope. When the telescope tube is unscrewed a simple microscope, or flea-glass, is revealed. By placing a specimen on the pin, it can be magnified using the small lens. This method of observation was also used by Hooke when making his drawings for Micrographia.

Micrographia contains observations made with the aid of magnifying lenses; some of these on very small things, some on astronomical bodies. Hooke's image of a flea (justly so - as we can all see here or in Neal's book) is famous; perhaps less well-known is his invention of the term 'cell' in a biological context as a result of his studies of cork. Micrographia includes a series of observations of lunar craters, and his speculation as to the origin of these features. Micrographia Restaurata is a condensed version published in 1745; it has briefer explanations, but has all the figures, nearly all of which were printed from Hooke's original plates.

A flea from Micrographia with a replica of Robert Hookes compound microscope

(based on an original dating from about 1665)

Achievements

In addition to Micrographia and Hooke's Law, Hooke invented the anchor escapement and may also have invented the balance spring before Christiaan Huygens. An escapement is a device for regulating the rate of a watch or clock, and the anchor escapement was a major step in accurate watch design. The balance spring is also used to regulate the flow of energy from the mainspring. It coils and uncoils with a natural periodicity, allowing for fine adjustment of the period of ticks. Modern spring watches still use balance springs, and the most common escapement today is the double roller Swiss anchor escapement, which is a nineteenth-century modification of Hooke's design.

Hooke is also often credited with inventing the compound microscope, a design consisting of multiple lenses (usually three - an eyepiece, a field lens and an objective). While he did give much advice on new microscope designs to the instrument maker Christopher Cock, this attribution appears to be incorrect.

His other significant achievements include the invention of the universal joint, the construction of the first Gregorian reflecting telescope, and the discovery of the first binary star.

Hooke and Newton

There was lots of mutual dislike between Hooke and Isaac Newton. It all started in 1672 when Hooke criticized Newton's presentation showing that prisms split white light rather than modifying it. Newton was furious that the hunchback Hooke was unable to grasp his ground-breaking discovery, and threatened to leave the Royal Society. In 1684, Newton failed to recognize Hooke's contribution to his Principia. The mutual dislike lasted till the end of Hooke's life. A Royal Society portrait of Hooke circa 1710 long thought lost was discovered recently[1]; Blame falls upon Newton as many believe he lost it.

More heat between Newton and Hooke: Gravity

Controversy between Hooke and Newton. The only real contention registered by Hooke was in regard to Newton's published work on Planetary Motion. In his Attempt to Prove the Motion of the Earth (1674), he offered a theory of planetary motion based on the correct principle of inertia and a balance between an outward centrifugal force and an inward gravitational attraction to the Sun. In 1679, in a letter to Newton, he finally suggested that this attraction would vary inversely as the square of the distance from the Sun. History knows Hooke wrote a letter to Newton in 1679 explaining his theories on planetary motion which he considered to be a force continuously acting upon the planet and diverting it from a straight path. Newton wrote back explaining his theory of the Earth's rotation, providing a sketch showing the path of a falling object spiralling towards the centre of the earth. Newton admitted his own drawing was wrong but 'corrected' Hooke's sketch based on his (Newton's) theory that the force of gravity was a constant when Hooke replied that his (Hooke's) theory of planetary motion would make the path of the falling object an ellipse - providing a sketch to demonstrate his argument. It is important to note here that Hooke wrote again to Newton stating that he (Hooke) considered gravity to involve an inverse square law. Gravity isn't a constant as Hooke could empirically prove.

Sir Isaac Newton's Principia Mathematica prepared April 1687 and sent to Doctor Edmund Halley for publication caused Hooke to claim priority over the realization of the inverse square law of gravity. Newton had made no mention in his first edition of Hooke's contribution, but did make some amends in the second edition. Newton tried to prevent the publication of the third edition in reaction to these claims. Hooke's 1662 voyage to the West Indies helped him discover how gravity changes (with a weaker attraction) near the equator inspired his application of the Inverse square law in regards to planetary motion shown here under the Principia Mathematica link. Hooke's contemporaries may have had difficulties in grasping this concept for in 1684 Wren, Hooke, and Halley discussed at the Royal Society, whether the elliptical shape of planetary orbits was a consequence of an inverse square law of force depending on the distance from the Sun. Halley wrote that Robert Hook says he has the answer but would not publish it for some time so that others (Newton?) trying and failing might know how to value it. Newton tried to prevent the publication of the third edition in reaction to these claims. Fifty years later, after the death of Hooke when Newton wrote his own recollections of these events, the account he gives disagrees with the historical facts and records surviving this period. These records are available for inspection today.

When Newton became the President of the Royal Society in 1703 - the year Hooke died - and his duties would have involved the responsibility of the society's repository, including the various donations by fellows of the society. Many of Hooke's contributions have been lost or dispersed without record as to what happened to them. Hooke's design for a marine chronometer was rediscovered only in 1950 at the Library of Trinity College, Cambridge. Conjecture may suggest that Newton acted deliberately in losing many important works. Many other causes could have contributed to the loss of these items although it might be considered that Newton had motives to imply culpability.

Longitude

Robert Hooke had already produced possible solutions 100 years earlier. The critical component in 17th and 18th century clocks was the pendulum, which itself was dependent on gravity as part of its driving/controlling force. Robert Hooke voyaged to the West Indies in 1662, discovering how gravity changes (with a weaker attraction near the equator) and humidity interfered with the accuracy of a clock.

He also realised the movement of the ship added additional errors to the pendulum's swing. To overcome these issues he invented counterwound spiral springs & double balances that compensated for these variable forces on the pendulum. He then designed a marine chronometer employing these improvements and created a pocket watch utilising his compensating devices. The new timepiece was demonstrated 20th Feb. 1668 to the Royal Society! Does someone smell a Newton?

Enter John Harrison

While it was the Longitude Act of 1714 that brought John Harrison to London, The Royal Society saw the H-5 ninety-nine years later in 1761 when the English horologist John Harrison built a portable instrument with a compensation mechanism to ensure that the length of the pendulum was independent of temperature and its workings were unaffected by the movement of the ship. If John Harrison had been able to discover the earlier design by Hooke (later discovered in 1950 at Trinity College, Cambridge), it would have undoubtedly made his task easier!

As to how the design became 'rested' at Trinity College nor why it was never catalogued which would have made its discovery possible by John Harrison and other clock-makers involved with trying to determine longitude accurately at sea could be explained by examining the actions of one other.

It would be a disservice to not say Harrison truly understood the importance in his choice of using of the right materials for the chronometers. He likely created the field of materials science singlehandedly. The engineering of near-frictionless surfaces and self-lubricating parts is only part of Harrison's genius.

His was a triumph for the mechanics.

Related entries

- Robert Boyle

- Boyle's Law, aka Hooke's, Boyle's, and Mariotte's Law (Neal Stephenson)

- Christiaan Huygens

- Isaac Newton

- Principia Mathematica

- Micrographia

- microscope

- Royal Society

- Longitude

External links

- Hooke's Portraits

- Micrographia

- Micrographia Restaurata

- Robert Hooke - Inspirational Father of Modern Science in England

- Biography of Robert Hooke

- BBC on Hooke

- Another biography

- Robert Hooke Resources

- Robert Hooke's family and birthplace

- "England's Leonardo". A lecture by Allan Chapman

- Robert Hooke Tercentenary Conference

- Robert Hooke Imagery via Google.