Stephenson:Neal:Cryptonomicon:22:A thousand sailors in white (Alan Sinder)

From the Quicksilver Metaweb.

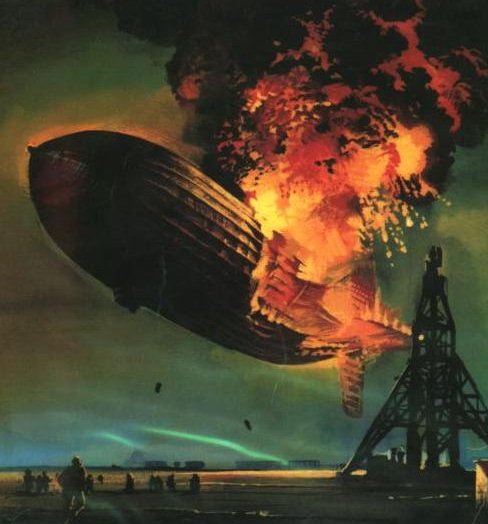

The Cryptonomicon page on the Hindenburg disaster that should make you really wonder about the angels Lawrence Waterhouse saw

Stephensonia

*Neal takes us to May 6, 1937's famous Hidenburg disaster:

A thousand sailors in white were standing in a ring around the long flame. One of them held up his hand and waved Lawrence down. Lawrence came to a stop next to the sailor and planted one foot on the sand to steady himself. He and the sailor stared at each other for a moment and then Lawrence, who could not think of anything else, said, "I am in the Navy also." Then the sailor seemed to make up his mind about something. He saluted Lawrence through, and pointed him towards a small building off to the side of the fire.

The building looked only like a wall glowing in the firelight, but sometimes a barrage of magnesium blue light made its windowframes jump out of the darkness, a rectangular lightning-bolt that echoed many times across the night. Lawrence started pedaling again and rode past that building: a spiraling flock of alert fedoras, prodding at slim terse notebooks with stately Ticonderogas, crab-walking photogs turning their huge chrome daisies, crisp rows of people sleeping with blankets over their faces, a sweating man with Brilliantined hair chalking umlauted names on a blackboard. Finally coming around this building he smelled hot fuel oil, felt the heat of the flames on his face and saw beach--glass curled toward it and desiccated.

He stared down upon the world's globe, not the globe fleshed with continents and oceans but only its skeleton: a burst of meridians, curving backwards to cage an inner dome of orange flame. Against the light of the burning oil those longitudes were thin and crisp as a draftsman's ink-strokes. But coming closer he saw them resolve into clever works of rings and struts, hollow as a bird's bones. As they spread away from the pole they sooner or later began to wander, or split into bent parts, or just broke off and hung in the fire oscillating like dry stalks. The perfect geometry was also mottled, here and there, by webs of cable and harnesses of electrical wiring. Lawrence almost rode over a broken wine bottle and decided he should now walk, to spare his bicycle's tires, so he laid the bike down, the front wheel covering an aluminum vase that appeared to have been spun on a lathe, with a few charred roses hanging out of it. Some sailors had joined their hands to form a sort of throne, and were bearing along a human-shaped piece of charcoal dressed in a coverall of immaculate asbestos. As they walked the toes of their shoes caught in vast, ramified snarls of ropes and piano-wires, cables and wires, creative furtive movements in the grass and the sand dozens of yards every direction. Lawrence began planting his feet very thoughtfully one in front of the other, trying to measure the greatness of what he had come and seen. A rocket-shaped pod stuck askew from the sand, supporting an umbrella of bent-back propellers. The duralumin struts and cat walks rambled on above him for miles. There was a suitcase spilled open, with a pair of women's shoes displayed as if in the window of a down town store, and a menu that had been charred to an oval glow, and then some tousled wall-slabs, like a whole room that had dropped out of the sky--these were decorated, one with a giant map of the world, great circles arcing away from Berlin to pounce on cities near and far, and another with a photograph of a famous, fat German in a uniform, grinning on a flowered platform, the giant horizon of a new Zeppelin behind him.

After a while he stopped seeing new things. Then he got on his bicycle and rode back through the Pine Barrens. He got lost in the dark and so didn't find his way back to the fire tower until dawn. But he didn't mind being lost because while he rode around in the dark he thought about the Turing machine. *

Authored entries

- TBA

Hindenburg disaster

On May 6, 1937, at 19:25 the German zeppelin Hindenburg caught fire and was utterly destroyed within a minute while attempting to dock with its mooring mast at Lakehurst Naval Air Station in New Jersey. Of the 97 people on board, 35 died (13 passengers, 22 crew-members and one ground crew member).

Infamous Hindenburg Zeppelin which on May 6, 1937 was

destroyed when its hydrogen gas-filled envelope caught fire

The Hindenburg

The LZ-129 Hindenburg and her sister-ship LZ-130 "Graf Zeppelin II" were the two largest aircraft ever built. The Hindenburg was named after the President of Germany, Paul von Hindenburg. It was a brand-new all aluminium design: 245 m long (804 feet), 41 m in diameter (135 ft), containing 211,890 m³ of gas in 16 bags or cells, with a useful lift of 112 tons, powered by four 1100 horsepower (820 kW) engines giving it a maximum speed of 135 km/h (83 mph). It could carry 72 passengers (50 transatlantic) and had a crew of 61. For aerodynamic reasons the passenger quarters were contained within the body rather than in gondolas. It was skinned in cotton, doped with iron oxide and cellulose acetate butyrate impregnated with aluminium powder. Constructed by Luftschiffbau Zeppelin in 1935 at a cost of £500,000, it made its first flight in March 1936 and completed a record double-crossing in five days, 19 hours, 51 minutes in July.

The Hindenburg was intended to be filled with helium but a United States military embargo on helium forced the Germans to use highly flammable hydrogen as the lift gas. Knowing of the risks with the hydrogen gas, the engineers used various safety measures to keep the hydrogen from causing any fire when it leaked, and they also treated the airship's coating to prevent electric sparks that could cause fires.

The Disaster: Historic Newsreel Coverage

The disaster is remembered because of extraordinary newsreel coverage, photographs, and Herbert Morrison's recorded radio eyewitness report from the landing field. Morrison's words were not broadcast until the next day. Parts of his report were later dubbed onto the newsreel footage (giving an incorrect impression to some modern eyes accustomed to live television that the words and film had always been together). Morrison's broadcast remains one of the most famous in history his plantive words "oh the humanity" resonate with the memory of the disaster.

Herbert Morrison's famous words should be understood in the context of the broadcast, in which he had repeatedly referred to the large team of people on the field, engaged in landing the airship, as a "mass of humanity." He used the phrase when it became clear that the burning wreckage going to settle onto the ground, and that the people underneath would probably not have time to escape it. It is not clear from the recording whether his actual words were "Oh, the humanity" or "all the humanity."

There had been a series of other airship accidents (none of them Zeppelins) prior to the Hindenburg fire, most due to bad weather. However, Zeppelins had accumulated an impressive safety record. For instance, the Graf Zeppelin had flown safely for more than 1.6 million km (1 million miles) including making the first complete circumnavigation of the globe. The Zeppelin company was very proud of the fact that no passenger had ever been injured on one of their airships.

But the Hindenburg accident changed all that. Public faith in airships was completely shattered by the spectacular movie footage and impassioned live voice recording from the scene. Because of this vivid publicity, Zeppelin transport came to an end. It marked the end of the giant, passenger-carrying rigid airships.

Controversies

Questions and controversy surround the accident to this day. There are two major points of contention: 1. How the fire started and 2. Why the fire spread so quickly.

At the time, sabotage was commonly put forward as the cause of the fire, in particular by Hugo Eckener, former head of the Zeppelin company and the "old man" of the German airships. The Zeppelin airships were widely seen as symbols of German and Nazi power. As such, they would have made tempting targets for opponents of the Nazis. However, no firm evidence supporting this theory was produced at the formal hearings on the matter.

Smaller Public Domain

Image of the Disaster

Although the evidence is by no means conclusive, a reasonably strong case can be made for an alternative theory that the fire was started by a spark caused by static buildup. Proponents of the "static spark" theory point to the following:

The airship's skin was not constructed in a way that allowed its charge to be evenly distributed and the skin was separated from the aluminium frame by nonconductive ramie cords. The ship passed through a moist weather front. The mooring lines were wet and therefore conductive. As the ship moved through the moist air the skin became charged. When the wet mooring lines connected to the aluminium frame touched the ground they grounded the aluminium frame. The grounding of the frame caused an electrical discharge to jump from the skin to the grounded frame. Witnesses reported seeing a glow consistent with a St. Elmo's fire.

The controversy around the rapid spread of the flames centres around whether blame lies primarily with the use of hydrogen gas for lift or the flammable coating used on the outside of the envelope fabric.

Proponents of the "flammable fabric" theory contend that the extremely flammable iron oxide and aluminium impregnated cellulose acetate butyrate coating could have caught fire from atmospheric static, resulting in a leak through which flammable hydrogen gas could escape. After the disaster the Zeppelin company's engineers determined this skin material, used only on the Hindenburg, was more flammable than the skin used on previous craft. Cellulose acetate butyrate is of course flammable but iron oxide increases the flammability of aluminium powder. In fact iron oxide and aluminium can be used as components of solid rocket fuel.

Hydrogen burns invisibly (emitting light in the UV range) so the visible flames (see photo) of the fire could not have been caused by the hydrogen gas. Also motion picture films show downward burning. Hydrogen, being less dense than air, burns upward. Some speculate that the German government placed the blame on flammable hydrogen in order to cast the U.S. helium embargo in a bad light.

Also, the naturally odorless hydrogen gas in the Hindenburg was 'odorised' with garlic so that any leaks could be detected, and nobody reported any smell of garlic during the flight or at the landing prior to the disaster.

It is also pointed out that none of the victims died burned by hydrogen. Of the 35 victims, 33 died because they jumped out of the airship.

Opponents of the "flammable fabric" theory contend that it is a recently developed analysis focused primarily on deflecting public concern about the safety of hydrogen. These opponents contend that the "flammable fabric" theory fails to account for many important facts of the case.

Related entries

External links

- Hindenburg Disaster Newsreel Footage

- The Hindenburg (1975 Movie) The Hindenburg (1975 Movie)

- An Article Supporting the Flammable Fabric Theory

- An Article Rejecting the Flammable Fabric Theory

- "Hindenburg in Flames"

- Navy Lakehurst Historical Society, Inc a non-profit organization dedicated to preserving the distinguished heritage of Naval Air Station Lakehurst.

References

Duggan, John (2002). LS 129 "Hindenburg" The Complete Story . Ickenham, UK: Zeppelin Study Group. ISBN 0-9514114-8-9 .