Stephenson:Neal:Cryptonomicon:343:just a Gedankenexperiment (Alan Sinder)

(Redirected from Gedankenexperiment)

This is the Cryptonomicon page for Gedankenexperiment. Repeat to yourself Xeno is AKA Zeno

Stephensonia

Ala the Saturday Night Live* WWII Spies routine: "Who won the World Series in 1934?" damn spies!

"You are assuming that the Germans have not already broken that code," Root says, pointing a bloody and accusing finger at Benjamin's big tome of gibberish. "But maybe they have. They've been sinking our convoys left and right, you know. If that's the case, then there is no negative in letting it fall into their hands."

"But that contradicts your theory about the secret convoy!" Benjamin says.

"The secret convoy was just a Gedankenexperiment,"Root says.

Corporal Benjamin rolls his eyes; apparently, he actually knows what that means. "If they've already broken it, then why are we going to all of this trouble, and risking our lives to GIVE IT TO THEM!?"

Root ponders that one for a while. "I don't know."

"Well, what do you think, Lieutenant Root?" Bobby Shaftoe asks a few excruciatingly silent minutes later.

"I think that in spite of my Gedankenexperiment, that Corporal Benjamin's explanation -- i.e., that Lieutenant Monkberg is a German spy -- is more plausible."

Benjamin lets out a sigh of relief. Monkberg stares up into Root's face, paralyzed with horror.

It's always something Damn spies!!*

Authored entries

- Stephenson:Neal:Quicksilver:83:Translated into the Analytical language...(Alan Sinder)

- Stephenson:Neal:Quicksilver:165:Zeno's Paradox (Matt Zwolinski)

- Stephenson:Neal:Quicksilver:804:in fact it was a vector (Olivier Gerard)

- Heinlein:Robert:Have Space Suit Will Travel:40:Almost halfway to the Moon, I'd say (Neal Stephenson)

- Gedankenexperiment (Jeremy Bornstein)

Wikipedia: Gedankenexperiment

In physics and other fields, a thought experiment (from the German Gedankenexperiment) is an attempt to solve a problem using the power of human imagination. These experiments are used to attempt to understand something about the universe. Thought experiments have been used to pose questions in philosophy at least since Greek antiquity; a famous example is Plato's Cave, but others pre-date Socrates. In physics and other sciences many famous thought experiments date from the nineteenth and especially the twentieth century, but examples can be found at least as early as Galileo.

Many thought experiments include apparent paradoxes about the known or accepted, that with time have led to the reformulation or precision of theories. A set of examples from Ancient history are Xeno's Paradoxes. These included the idea that motion could be theoretically impossible. To get from A to B, one must first cross point C at the midpoint, then D at the next midpoint (between C and B) and so on. There are an infinity of these points that you must cross, and since one can never complete an infinite number of tasks, one can never reach B. This particular paradox has been attacked by many people with many different ideas on the ontology of spacetime. Other experiments, such as Albert Einstein's twins paradox, have been absorbed into scientific orthodoxy.

Zeno's Paradoxes

Zeno's paradoxes are a set of paradoxes conceived by Zeno of Elea to support Parmenides's doctrine that all evidence of the senses is misleading, and particularly that there is no motion.

Several of Zeno's eight surviving paradoxes (preserved in Aristotle's Physics and Simplicius's commentary thereon) are essentially equivalent to one another; and most of them were regarded, even in ancient times, as very easy to refute. Three of the strongest and most famous--that of Achilles and the tortoise, that of a rock thrown at a tree, and that of an arrow in flight--are given here.

Zeno's paradoxes may seem trivial today, but they were a major problem for ancient and medieval philosophers, who found no satisfactory solution until the 17th century, with the mathematical results on infinite sequences and calculus. Indeed, it appears very reasonable that their correct resolution wasn't actually acheived until the 21st century, with the work of Peter Lynds on time, motion and position.

Achilles and the tortoise

In the paradox of Achilles and the tortoise, we imagine the Greek hero Achilles in a footrace with the plodding reptile. Because he is so fast a runner, Achilles graciously allows the tortoise a head start of a hundred feet. If we suppose that each racer start running at some constant speed (one very fast and one very slow), then after some finite time, Achilles will have run a hundred feet, bringing him to the tortoise's starting point; during this time, the tortoise has "run" a (much shorter) distance, say one foot. It will then take Achilles some further period of time to run that distance, during which the tortoise will advance farther; and then another period of time to reach this third point, while the tortoise moves ahead. Thus, whenever Achilles reaches somewhere the tortoise has been, he still has farther to go. Therefore, Zeno says, swift Achilles can never overtake the tortoise.

In the modern analysis, the paradox is resolved with the fundamental insight of calculus that a sum of infinitely many terms can yield a finite result. Adding the (infinitely many) times together that Achilles needs to reach the previous positions of the tortoise results in a finite total time, and that is indeed the time when Achilles overtakes the tortoise.

The rock thrown towards a tree

The next paradox, that of the rock thrown towards a tree, is a variant of the previous one. Now Zeno stands eight feet from a tree, holding a rock. He throws his rock at the tree. Before the rock can reach the tree, it must traverse half the eight feet. It will take some finite time for the rock to fly four feet. After that time, it will still have four feet to go, and to traverse that distance must first cover half of it: two feet, and more time. After it travels two feet, it must travel one foot, then half a foot, then a quarter foot, and so on ad infinitum. Therefore, Zeno concludes, the rock can never hit the tree.

The Arrow Paradox

Finally, in the arrow paradox, we imagine an arrow in flight. At every moment in time, the arrow is located at a specific position. If the moment is just a single instant, then the arrow does not have time to move and is at rest during that instant. Now, during the following instances, it then must also be at rest for the same reason. The arrow is always at rest and cannot move: motion is impossible.

This paradox is resolved by calculus as follows: in the limit, as the length of a moment approaches zero, the instantaneous rate of change or velocity (which is the quotient of distance over length of the moment) does not have to approach zero. This nonzero limit is the velocity of the arrow at the instant.

- Zeno's Arrow

- Zeno's Arrow applied to Atomism -- Zenos argument that an (apparently) moving arrow is really at rest throughout its flight seems easy to evade if one insists that space is continuous (and hence infinitely divisible). But an atomist who insists on theoretically indivisible atoms seems bound to deny that space is infinitely divisible. And Zenos Arrow Paradox poses an especially troubling problem for such an atomist....

Wikipedia: Twin paradox

The Twin paradox is a thought experiment in special relativity (SR): of two twin brothers, one undertakes a long space journey while the other remains on Earth. When the traveller finally returns to Earth, it is observed that he is younger than the twin who stayed put.

This outcome is predicted by special relativity ("time dilation of moving clocks") a phenomenon which has been verified experimentally, for example with muons produced in the upper atmosphere being detectable on the ground. Without time dilation, the muons would decay long before reaching the ground.

The apparent paradox arises if one takes the position of the travelling twin: from his perspective, his brother on Earth is moving away quickly, and eventually comes close again. So the traveller can regard his brother on Earth to be a "moving clock" which should experience time dilation. Special relativity says that all observers are equivalent, and no particular frame of reference is privileged. Hence, the travelling twin, upon return to Earth, would expect to find his brother to be younger than himself, contrary to that brother's expectations. Which twin is correct?

It turns out that the travelling twin's expectation is mistaken: special relativity does not say that all observers are equivalent, only that all observers in inertial frames are equivalent. But the travelling twin jumps frames when he does a U-turn. The twin on Earth rests in the same inertial frame for the whole duration of the flight (if we ignore the comparatively small acceleration resulting from Earth's mass and movement) and he is therefore able to distinguish himself from the travelling twin.

The confusion arises because there are not two but three relevant inertial frames: the one in which the stay-at-home twin remains at rest, the one in which the travelling twin is at rest on his outward trip, and the one in which he is at rest on his way home. It is during the U-turn, when the traveling twin switches frames, that he must adjust the calculated age of the twin at rest. This is a purely artificial effect caused by the change in the definition of simultaneity when changing frames. Here's why.

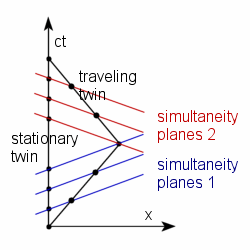

In special relativity there is no concept of absolute present. A present is defined as a set of events that are simultaneous from the point of view of a given observer. The notion of simultaneity depends on the frame of reference, so switching between frames requires an adjustment in the notion of the present. If one imagines a present as a (three-dimensional) simultaneity plane in Minkowski space, then switching frames results in changing the inclination of the plane.

In the spacetime diagram on the right, the first twin's lifeline coincides with the vertical axis (his position is constant in time). On the first leg of the trip, the second twin moves to the right (black sloped line); and on the second leg, back to the left. Blue lines show the planes of simultaneity for the traveling twin during the first leg of the journey; red lines, during the second leg. During the U-turn the plane of simultaneity jumps from blue to red and quickly sweeps a large segment of the lifeline of the resting twin. Suddenly the resting twin ages very fast in the reckoning of the traveling twin.

In resolving the paradox, it is sometimes claimed that special relativity cannot be applied to accelerating bodies, and that general relativity has to be used, but this is not correct. For instance, the age of both the Earthbound and travelling twin can be correctly calculated by integrating the spacetime interval (or proper time) over the spacetime paths they make in any inertial frame (these paths are known as the twin's worldlines). Similar methods can be used to calculate the relativistic behaviour of an accelerating spacecraft (see relativistic rocket). SR only becomes inapplicable when the effect of gravity is non-negligible, in which case general relativity must be used.

Related entries

- Principle of Equivalence Gedankenexperiment

- Einstein's Principle of Equivalence

- Albert Einstein

- Heinlein:Robert:Have Space Suit Will Travel

- Einstein's Principle of Equivalence

- Calculus

- Constant

- Vector

- Scalar

- Algebra

- Low earth orbit (LEO)

- Kinetic energy

- Numerical techniques

- Squared

- Meters per second squared

- Mass

- Meter

External links

- http://www.newtonphysics.on.ca/EINSTEIN/Chapter10.html

- http://altair.syr.edu:2024/lightcone/equivalence.html

- F. W. Sears, Principles of Physics, Addison-Wesley, p. 267, 1946

ISBN 0738200239 The Einstein Paradox: And Other Science Mysteries Solved by Sherlock Holmes AKA The Strange Case of Mrs. Hudson's Cat by Colin Bruce - he uses a train instead of a elevator but the scheme is the same. Einstein for the Mathphobic.

ISBN 0738205893 Conned Again, Watson! Cautionary Tales of Logic, Math, and Probability by Colin Bruce: there has never been a more exciting way to learn when to take a calculated risk-and how to spot a scam. * Thought Experiments * Philosophy Encyclopedia - Zeno * Internet Encyclopedia - Zeno * Zeno * Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy * S. Marc Cohen - whose lectures appear below * Zeno's race course part 1 * Why Zeno is unsound * Zeno's race course part 2 * Zeno's Arrow * Zeno's Arrow applied to Atomism

This Frank & Ernest cartoon may help in understanding when Zeno is practical for humans.