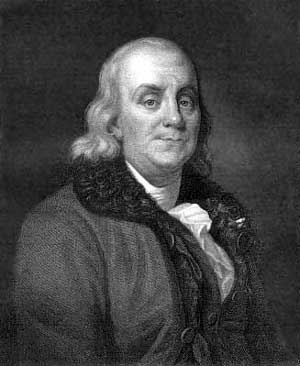

Benjamin Franklin

From the Quicksilver Metaweb.

This is the Quicksilver page for Benjamin Franklin.

Stephensonia

Appears at the beginning of Quicksilver -- as an eager eight year boy to show Enoch Root around Boston. Enoch deems the lad dangerous. Young Ben expresses the wish to join the Royal Society when he is of age. The real Ben Franklin did join the Lunar Society and the Royal Society.

Authored entries

- Erasmus Darwin (Andrew Berry)

- Brain Tanning (Timberbee)

- Stephenson:Neal:Quicksilver:6: bits of slaughtered animals (Alan Sinder)

- Stephenson:Neal:Quicksilver:7:Ben. Son of Josaiah. (Gary Thompson)

- Stephenson:Neal:Quicksilver:8:Barker (Neal Stephenson)

- Stephenson:Neal:Quicksilver:8:King Carlos the Sufferer(Alan Sinder)

- Stephenson:Neal:Quicksilver:9: a loud fellow (Alan Sinder)

- Stephenson:Neal:Quicksilver:10:D.G. HISPAN ET IND REX (Alan Sinder)

- Stephenson:Neal:Quicksilver:17:...Oh Dear...(Alan Sinder)

- Stephenson:Neal:Quicksilver:20:A harder question (Jeremy Bornstein)

- Stephenson:Neal:Quicksilver:21:Killed a great deal of Irishmen (Alan Sinder)

- Stephenson:Neal:Quicksilver:21:granted all men - even Jews - the right to worship (Alan Sinder)

- Stephenson:Neal:Quicksilver:21:Mister Clarke had to get in line (Alan Sinder)

- Stephenson:Neal:Quicksilver:22:Monsieur Le Febure (Neal Stephenson)

- Stephenson:Neal:Quicksilver:22:T'was all rubbish (Alan Sinder)

- Stephenson:Neal:Quicksilver:22: anointed him with angelbalm, a thousand years old (Alan Sinder)

- Stephenson:Neal:Quicksilver:22:John Wilkins...Cryptonomicon (Neal Stephenson)

- Stephenson:Neal:Quicksilver:91:Atlantic is striped with currents (Chris Swingley) (Contributions to oceanography)

- Stephenson:Neal:Quicksilver:108:Mayflower (Alan Sinder)

- Stephenson:Neal:Quicksilver:442:arsch-leders (Jeremy Bornstein) - leather is leather

- Stephenson:Neal:Quicksilver:463:L'Emmerdeur (Jeremy Bornstein)

- Stephenson:Neal:The Confusion:8:Moseh de la Cruz (Alan Sinder)

Community entry: Ben Franklin

Ben studied philosophy and science extensively. His practical experimentation lead to the development of uniquely Benjamin Franklin inventions. Such as: the chimney-on-the-bottom "Franklin Stove," bifocal eyeglasses, even a Glass Harmonica.

Benjamin Franklin This musical instrument, the "armonica", was so intense that some regions outlawed it's use for fear that people would pass out and go into trances listening to it.

Ever intrigued by the phenomenon of electricity, the Kite-and-Key + Thunderstorm = Proof of Electro-Discharge experiment brought forth the Lightning Rod, and serious recognition from leading scientists in England and on the Continent. The terms "plus" and "minus" for electrical charge are his. A "minus" charge is an excess of electrons, which annoys some more even than harmonicas.

He also seemed to find particular joy in the expression of thought through logographics -- ideograms that force one to pronounce absent words. An "eye" for I, a "bee" for Be. Etc.

Dr. Franklin started the first lending library in North America.

He invented the catheter, the battery, and bifocals. He mapped the Gulf Stream in his spare time.

Franklin is a key Enlightenment figure, notably mostly for the degree to which he influenced politics. Most of the natural philosophers in Europe got in trouble with the authorities, were sent into exile, imprisoned, or worse. They had an influence on say the French Revolution but not directly. Meanwhile, those in North America started the American Revolution, took over, and developed a secular humanist government, some of its structures based in part on what they observed among native peoples, in particular, those of the Haudenosaunee, or "Iroquois" (a French word loaned from the Algonkian word meaning "serpent"), who had practiced a form of constitutional government for centuries prior to the arrival of the Europeans.

Franklin was a notorious con artist. He often published false statements for commercial advantage in his Almanack, including a spurious obituary for his chief rival Titus Leeds - causing Leeds great difficulties. Casual lying to get what he wanted was apparently a more or less innate trait of Franklin's - he was a womanizer and quite popular in part for his ability to manipulate and connive. In one famous incident, to get a seat in a crowded inn, he demanded a plate of oysters for his horse, who would eat only those. An amazed crowd went out to see the horse eat the oysters while Franklin selected a set from those vacated. When the innkeeper came back in and said "he won't eat them, sir", Ben said "well then give them to me and get that oaf some oats."

Today Franklin might well be considered a pathological liar. Which does not contradict being a good politician.

Benjamin Franklin

Benjamin Franklin (January 17, 1706 - April 17, 1790) was an American journalist, publisher, author, philanthropist, public servant, scientist, diplomat, and inventor who was also one of the leaders of the American Revolution, known also for his many quotations and his experiments with electricity. He corresponded with members of the Lunar Society and was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society. In 1775, Franklin became the first US Postmaster General.

Early Years

He was born on Milk Street, Boston, on January 17, 1706. His father, Josiah Franklin, was a tallow chandler who married twice. Benjamin was the youngest son of the seventeen children these two marriages produced. His schooling ended at ten, and at twelve he was bound as an apprentice to his brother James, a printer who published the New England Courant.

He eventually became a contributor to this publication and for a time was its nominal editor. During this time, he wrote a series of letters to the editor under the pseudonym of a spinster named "Silence Dogood"[1] which criticized public drunkenness, hoop petticoats, and especially Harvard College where, she claimed, students learnt nothing other than how to be conceited. The brothers quarreled, and Benjamin ran away, going first to New York, and thence to Philadelphia, where he arrived in October, 1723.

He soon obtained work as a printer, but after a few months he was induced by Governor Keith to go to London, where, finding Keith's promises empty, he again worked as a compositor in a printer's shop until he was brought back to Philadelphia by a merchant named Denman, who gave him a position in his business. On Denman's death Franklin returned to his former trade, and soon set up a printing house of his own from which he published The Pennsylvania Gazette, to which he contributed many essays and which he made a medium for agitating for a variety of local reforms. His intelligence combined with a great deal of savvy about cultivating a positive image of an industrious and intellectual young man earned him a great deal of social respect.

In 1732 he began to issue the famous Poor Richard's Almanac(with content both original and borrowed), on which a lot of his popular reputation is based. , Sayings from this almanac such as "A penny saved is a penny earned", are now commonly quoted every day by people all over the world.

Middle years

In 1758, the year in which he ceased writing for the Almanac, he printed in it "Father Abraham's Sermon", now regarded as the most famous piece of literature produced in Colonial America.

Meanwhile, Franklin was concerning himself more and more with public affairs. He set forth a scheme for an Academy, which was taken up later and finally developed into the University of Pennsylvania, and he founded an American Philosophical Society for the purpose of enabling scientific men to communicate their discoveries to one another. He had already begun the electrical research that, along with other scientific inquiries, would occupy him for the rest of his life (in between bouts of politics and money-making).

In 1748 he sold his business in order to get leisure for study, having now acquired comparative wealth; and in a few years he had made discoveries that gave him a reputation with the learned throughout Europe. These include his investigations of electricity. Franklin identified positive and negative electrical charges and also demonstrated that lightning was electrical.

Franklin promoted this theory through the famous, though extremely dangerous, experiment of flying a kite during a lightning storm. It has been recently questioned whether or not Franklin actually did perform this experiment; the question remains controversial. Franklin, in his writings, displays that he was cognizant of the dangers and alternative ways to demonstrate that lightning was electrical. If Franklin did perform this experiment, he did not do it in the way that is often described (as it would have been dramatic but fatal). [2]

Franklin's inventions include the lightning rod, Franklin stove and bifocals. He was one of the best-known scientists of the 18th century. In recognition of his work with electricity, Franlin was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society and received its Copley Medal.

Franklin established two major fields of physical science, electricity and meteorology. In his classic work (A History of The Theories of Electricity & Aether), Sir Edmund Whittaker (p. 46) refers to Franklin's inference that electric charge is not created by rubbing substances, but only transferred, so that "the total quantity in any insulated system is invariable. This assertion is known as the principle of conservation of charge".

As a printer and a publisher of a newspaper, Franklin frequented the farmers' markets in Philadelphia to gather news. One day Franklin inferred that reports of a storm elsewhere in Pennsylvania must be the storm that visited the Philadelphia area in recent days. This initiated the notion that some storms travel, eventually leading to the synoptic charts of dynamic meteorology, replacing sole dependence upon the charts of climatology.

In 1751 Franklin and Dr. Thomas Bond obtained a charter from the Pennsylvania legislature to establish a hospital. Pennsylvania Hospital was the first hospital in what was to become the United States of America.

Political cartoon by Ben Franklin

This cartoon urged the colonies to join together

because of the French and Indian war

In politics he proved very able both as an administrator and as a controversialist; but his record as an office-holder is stained by the use he made of his position to advance his relatives. His most notable service in domestic politics was his reform of the postal system, but his fame as a statesman rests chiefly on his diplomatic services in connection with the relations of the colonies with Great Britain, and later with France. He was also involved in the creation of the first volunteer fire department, free public library, and many other civic enterprises.

In 1754 he headed the Pennsylvania delegation to the Albany Congress. This meeting of several colonies had been requested by the Board of Trade in England to improve relations with the Indians and defense against the French. Franklin proposed a broad Plan of Union for the colonies. While the plan was not adopted, elements of it found their way into the Articles of Confederation and the Constitution.

In 1757 he was sent to England to protest against the influence of the Penn family in the government of Pennsylvania, and for five years he remained there, striving to enlighten the people and the ministry of the United Kingdom as to colonial conditions. He also managed to secure a post for his son, William Franklin, as Governor of New Jersey.

Later years

On his return to America, he played an honorable part in the Paxton affair, through which he lost his seat in the Assembly, but in 1764 he was again dispatched to England as agent for the colony, this time to petition the King to resume the government from the hands of the proprietors. In London he actively opposed the proposed Stamp Act, but lost the credit for this and much of his popularity because he secured for a friend the office of stamp agent in America. Even his effective work in helping to obtain the repeal of the act did not regain his popularity, but he continued his efforts to present the case for the Colonies as the troubles thickened toward the crisis of the Revolution. This also led to an irreconcilable conflict with his son, who remained ardently loyal to the British Government.

In 1767 he crossed to France, where he was received with honor; but before his return home in 1775 he lost his position as postmaster through his share in divulging to Massachusetts the famous letter of Hutchinson and Oliver. On his arrival in Philadelphia he was chosen as a member of the Continental Congress and assisted in editing the Declaration of Independence.

In December of 1776 he was dispatched to France as commissioner for the United States. He lived in a home in the Parisian suburb of Passy donated by Jacques-Donatien Le Ray who would become a friend and the most important foreigner to help the United States win the war of independence. Ben Franklin remained in France until 1785, a favorite of French society. Franklin was so popular that it became fashionable for wealthy French families to decorate their parlors with a painting of him. He conducted the affairs of his country towards that nation with such success, which included securing a critical military alliance and negotiating the Treaty of Paris (1783), that when he finally returned, he received a place only second to that of George Washington as the champion of American independence.

When Franklin was recalled to America in 1785, Le Ray honored him with a commissioned portrait painted by Joseph Siffred Duplessis that now hangs in the National Portrait Gallery of the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, DC.

In addition, after his return from France in 1785, he became a slavery abolitionist who eventually became president of The Society for Promoting the Abolition of Slavery and the Relief of Negroes Unlawfully Held in Bondage.

While in retirement by 1787, he agreed to attend as a delegate at the meetings that would produce the United States Constitution to replace the Articles of Confederation. He is the only Founding Father who is a signatory of all three of the major documents of the founding of the United States, The Declaration of Independence, The Treaty of Paris and the United States Constitution.

Later, he finished his autobiography between 1771 and 1788, at first addressed to his son, then later completed for the benefit of mankind at the request of a friend.

Death and afterwards

He died on April 17, 1790 and was interred in the Christ Church burial grounds in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

At his death Franklin bequeathed £1000 (about $4400 at the time) to each of the cities of Boston and Philadelphia, in trust for 200 years. During the lifetime of the trust, Philadelphia used it for a variety of loan programs to local residents; from 1940 to 1990, the money was used mostly for mortgage loans. When the trust came due, Philadelphia decided to spend it on scholarships for local high school students. Boston used the gift to establish a trade school that, over time, became the Franklin Institute of Boston.

In recent years a number of anti-Semitic groups have been promoting a forged "quote" supposedly written by Benjamin Franklin. This quote has been debunked as a forgery by historians. (See WikiPedia:Neo-Nazi Theory (American founding fathers)).

Franklin's likeness adorns the American $100 bill. As a result, $100 bills are sometimes referred to in slang as "Benjamins" or "Franklins".

Franklin and the Hackers' Code

As well as being a polymath in the tradition of other great men during the Enlightenment, Benjamin Franklin embraced the hacker ethic that information wants to be free. We tend to think of Franklin as a man above all guided by the accumulation of wealth, but after he had made enough money he retired from his publishing and other businesses in 1748 at the age of 42 to pursue what he called "scientific amusements". In his day he was recognized as the most famous scientist alive and the foremost expert and experimenter with electricity. Some of his inventions, including the Franklin Stove, the lightning rod and the glass Armonica could have earned him a great deal of money, but he refused to patent any of them. He said in his Autobiography: "As we enjoy great advantages from the inventions of others, we should be glad of an opportunity to serve others by any invention of ours, and this we should do freely and generously."

Franklin, Pseudonyms, and Myth

Franklin's frequent use of pseudonyms in his writings, particularly in letters to the editor of his brother's paper and in his own Almanack, were intended to communicate arguments to the greater public which might be seen as risque, heretical, or possibly illegal or treasonous by the authorities. He also used them to present two sides of an issue.

When Franklin used a pseudonym, he often created an entire persona for the "writer." Sometimes he wrote as a woman, other times as a man, but always with a specific point of view. While all of his writings were focused and logical, many were also humorous, filled with wit and irony. Silence Dogood, Harry Meanwell, Alice Addertongue, Richard Saunders, and Timothy Turnstone were a few of the many pseudonyms Franklin used throughout his career[3].

Silence Dogood Mrs. Dogood was Franklin's first pseudonym, created when he was sixteen years old and serving as a printer's apprentice to his brother James. Silence Dogood was a middle-aged widow who looked at the world with a humorous and satiric eye. Her letters dealt with a range of topics from love and courtship to the state of education in Massachusetts. In all, fifteen Silence Dogood letters were published in James Franklin's New England Courant. The Silence Dogood letters have been used as a plot device in the recent movie "National Treasure" starring Nicholas Cage, in which the letters contain a code used to find a special pair of Franklin spectacles that are needed to see a treasure map hidden on the back of the Declaration of Independence. The treasure is allegedly the treasure of the Knights Templar which was hidden in the New World by Freemasons like Benjamin Franklin and Thomas Jefferson.

Caelia Shortface and Martha Careful Franklin wrote mocking letters from these two "ladies" to get even with his former employer Samuel Keimer for stealing some of Franklin's publishing ideas. The letters were printed in the American Weekly Mercury, a newspaper published by Keimer's competitor Andrew Bradford.

Busy Body Franklin's Busy Body letters were also published in the American Weekly Mercury. Miss Body's letters were filled with humorous looks at the battle of the sexes and barbs at local businessmen. Gossip was Busy Body's stock in trade.

Anthony Afterwit Franklin created this "gentleman" to provide a humorous look at matrimony and married life from a male point of view. Mr. Afterwit appeared in Franklin's Pennsylvania Gazette.

Alice Addertongue Miss Addertongue was a thirty-five year old gossip who provided Franklin's Pennsylvania Gazette with stories of scandal about prominent members of society.

Richard Saunders Of all of Franklin's noms de plume, Mr. Saunders became the best known. Richard Saunders was the "Richard" of Poor Richard's Almanack. First published late in 1732, Poor Richard's Almanack is probably Franklin's best-known publication. Richard Saunders' humorous sayings and advice filled the pages of the almanac's twenty-six editions.

Polly Baker Franklin used Polly Baker to examine the negative way women were treated in the eyes of the law. Ms. Baker had several illegitimate children and was punished for her "crime," while the fathers, many of whom were prominent citizens, suffered no such hardship.

Benevolus While in England, Franklin penned a number of letters under the name of Benevolus. These letters tried to answer some of the negative assertions made by the British press about the American colonists. These letters were published in London newspapers and journals.

Related entries

- Royal Society

- Stephenson:Neal:Quicksilver:Enoch Root (Connection with Enoch Root)

- Mary cCmndhd

- Erasmus Darwin

- Battery

- Gunpowder Plot

- Charles V

- Godfrey William Waterhouse

- Louis Joseph, Duke of Vendôme

- Tallow - historical

- Glorious Revolution

- English Civil War

- Oliver Cromwell

- Louis Joseph, Duke of Vendôme

- Talk:Hewing (Timberbee)

- Talk:Brain Tanning (Timberbee)

- Talk:Stephenson:Neal:Quicksilver:36:According to what scheme? (Alan Sinder)

- Talk:Stephenson:Neal:Quicksilver:576:rotten fish (Neal Stephenson)