Cotton Mather

From the Quicksilver Metaweb.

This is a Quicksilver intermediate page for Cotton Mather.

Stephensonia

Like Drake Waterhouse, Cotton is a Puritan pamphletteer

Authored entries

There are no authored entries yet.

Community entry: Cotton Mather

Mostly from Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia.

Cotton Mather (1664 -1728 ). B.A. 1678 (Harvard), M.A. 1681; honorary doctorate 1710 (University of Glasgow ). Son of Increase Mather. Socially and politically influential Puritan minister, prolific author, and pamphleteer.

Mather graduated from Harvard in 1678 at only 15 years of age. After completing his post-graduate work, he joined his father as assistant Pastor of Boston's Old North Church. It was not until his father's death in 1723 that Mather assumed full responsibilities as Pastor at the Church.

Author of more than 450 books and pamphlets, his ubiquitous literary works made him one of the most influential religious leaders in America. In his numerous writings, Mather set the nation's moral tone, and sounded the call for second and third generation Puritans whose parents had left England for the New England colonies of North America to return to the theological roots of Puritanism.

Cotton Mather was a friend of a number of the Judges charged with hearing the Salem Witch Trials, Mather urged the judges to give weight to spectral evidence. Writing of the trials later, Mather stated:

"If in the midst of the many Dissatisfactions among us, the publication of these Trials may promote such a pious Thankfulness unto God, for Justice being so far executed among us, I shall Re-joyce that God is Glorified..." (Wonders of the Invisible World).

Highly influential due to his prolific writing, Mather was a force to be reckoned with in secular as well as spiritual matters. After the fall of English King James II in 1688, Mather was among the leaders of a successful revolt against James' Governor of the consolidated Dominion of New England, Sir Edmund Andros .

Mather was influential in early American science as well. In 1716, as the result of observations of corn varieties, he conducted one of the first experiments with plant hybridization. This observation was memorialized in a letter to a friend:

"My friend planted a row of Indian corn that was colored red and blue; the rest of the field being planted with yellow which is the most usual color. To the windward side this red and blue so infected three or four rows as to communicate the same color unto them; and part of ye fifth and some of ye sixth. But to the leeward side, no less than seven or eight rows had ye same color communicated unto them; and some small impressions were made on those that were yet further off."

Of Mather's three wives and fifteen children, only one wife and two children survived him. Mather was buried on Copp's Hill.

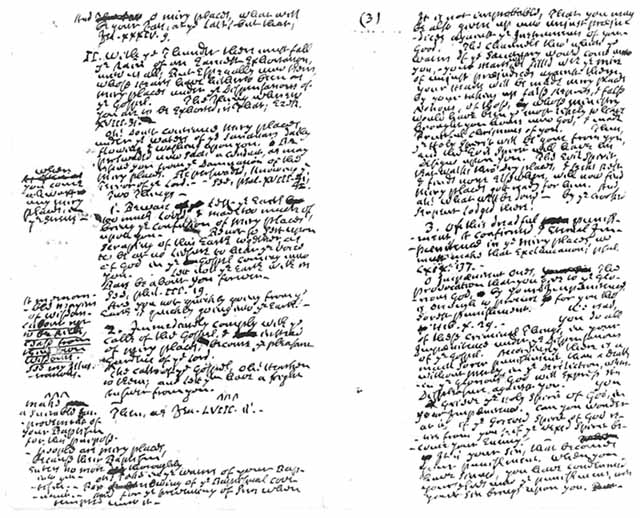

A Sermon by Cotton Mather

Mather's Major Works By Date

- Wonders of the Invisible World (1693)

- Magnalia Christi Americana (1702)

- Bonifacius (1710)

- The Christian Philosopher (1721)

- Religious Improvements (1721)

- Manuductio ad Ministerium (1726)

Witches

In 1692, in Salem Village, (now Danvers, Massachusetts ), a number of young girls, particularly Abigail Williams and Betty Parris, accused other townsfolk of magically possessing them, and therefore of being witches or warlocks. The community, besieged by Indians and dispossessed of their charter, the only form of government they had, believed the accusations, and sentenced these people to either confess they were witches or be hanged. The accusations spread quickly, and within only a couple of months had involved the neighboring communities of Andover, Amesbury, Salisbury, Haverhill, Topsfield, Ipswich, Rowley, Gloucester, Manchester, Maldon, Charleston, Billerica, Beverly, Reading, Woburn, Lynn, Marblehead, and Boston.

Why did the hysteria happen?

There are various theories as to why the community of Salem Village exploded into delusions of witchcraft and demonic interference. The most common one is that the Puritans, who governed Massachusetts Bay Colony with little royal intervention from its settlement in 1630 until the new Charter was installed in 1692, went through mass religion-induced hysterical delusion. Most modern experts view that as too simplistic an explanation. Other theories include child abuse, fortunetelling experiments gone amok, ergot -related paranoid fantasies (ergot is a fungus that grows on damp barley, producing a substance very similar to D-lysergic acid ; in a pre-industrial society, it is easy to accidentally ingest it), conspiracy by the Putnam family to destroy the rival Porter family, and societal victimization of women.

There was also great stress within the Puritan community. They had lost their charter in the Glorious Revolution of 1688, and in the spring of 1692 still did not know what their future would be. They were under constant Indian attack and could not depend on England at all for support; their militia came from the ranks of their young men, and in 1675 's King Philip's War their entire population had been decimated: one of ten European settlers in New England was killed by Indian attacks. Though that war was over, Indian raids and skirmishes were a constant hazard. More and more, New England was becoming a mercantile colony, and Puritans and non-Puritans alike were making a lot of money, which the Puritans saw as both necessary and sinful. And as the merchant class rose in status, the ministerial class declined.

Perhaps the most compelling new theory is that of Mary Beth Norton, who wrote In The Devil's Snare. Her thesis: that any or all of the above explanations likely played an important role, but Salem and the rest of New England, and particularly the north and northwest areas, were besieged by frequent Indian attacks, which created an atmosphere of fear that contributed greatly to the hysteria. Her evidence: most of the accused witches and most of the afflicted girls had strong societal or personal ties to Indian attacks over the preceding fifteen years. The accusers frequently referenced a "black man," discussed joint meetings between the alleged witches and Indians in sabbats, and described images of torture taken directly from tales of Indian captivity. In addition, Puritan clergy had, since King Philip's War in 1675, frequently referred to Indians as being of the devil, had associated them with witchcraft and, in pulpit-pounding sermons that lasted as long as five hours, expounded repeatedly about Satan and his devils besieging the Puritans, who were seen as the army of God. In short, the Indian had been associated in the New England Puritan mind as the Devil. Therefore, concerted Indian attacks were the Devil trying to bring down the Puritan society, and one should expect attacks from within as well as without. By 1691, Puritans were primed for witchcraft hysteria.

Salem Village itself was a microcosm of Puritan stress. Half the Village were farmers and supported the minister, Samuel Parris, and breaking away from Salem Town to form their own distinct township; the other half of the Village wanted to remain part of Salem Town, retain the merchant ties, and refused to contribute to the maintenance of Parris and his family. In addition, a number of refugees from recent Indian attacks in the Maine and New Hampshire regions had taken shelter with relatives in Salem, bringing tales of horror with them. As a result, by 1691 Salem Village was a powder keg, and the spreading possession of young girls was the spark that set it off.

In Context

Cotton Mather was a true believer in witchcraft. In 1688, he had investigated the strange behavior of four children of a Boston mason named John Goodwin. The children had been complaining of sudden pains and crying out together in chorus. He concluded that witchcraft, specifically that practiced by an Irish washerwoman named Mary Glover, was responsible for the children's problems. He presented his findings and conclusions in one of the best known of his 382 works, "Memorable Providences." Mather's experience caused him to vow that to "never use but one grain of patience with any man that shall go to impose upon me a Denial of Devils, or of Witches."

Mather urged the judges to consider spectral evidence, giving it such weight as "it will bear," and to consider the confessions of witches the best evidence of all. As the trials progressed, and growing numbers of person confessed to being witches, Mather became firmly convinced that "an Army of Devils is horribly broke in upon the place which is our center."

On August 4, 1692, Mather's sermon warned that the Last Judgment was near at hand, and portraying himself, Chief Justice Stroughton, and Governor Phips as leading the final charge against the Devil's legions. On August 19, when Mather was in Salem to witness the execution of ex-minister George Burroughs for witchcraft. When, on Gallows Hill, Burroughs was able to recite the Lord's Prayer perfectly (something that witches were thought incapable of doing) and some in the crowd called for the execution to be stopped. Mather reminded those gathered that Burroughs had been duly convicted by a jury. Mather was given the official records of the Salem trials for use in preparation of a book that the judges hoped would favorably describe their role in the affair. The book, "Wonders of the Invisible World," provides facinating insights both into the trials and Mather's own mind.

When confessed witches began recanting their testimony, Mather may have begun to have doubts about at least some of the proceedings. He revised his own position on the use of spectral evidence and tried to minimize his own large role in its consideration in the Salem trials. Later in life, Mather turned away from the supernatural and may well have come to question whether it played the role it life he first suspected.

FYI

Cotton Mather also has links to pirates. * Cotton Mather - "The Vial Poured Out Upon the Sea: A Remarkable Relation of Certain Pirates Brought Unto a Tragical and Untimely End: Some conferences with them."