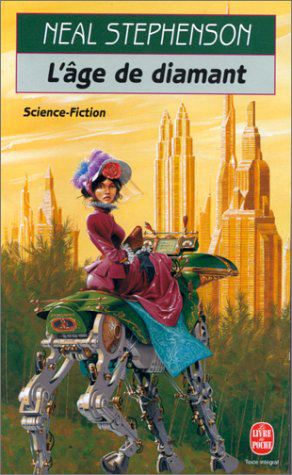

Stephenson:Neal:The Diamond Age, or A Young Lady's Illustrated Primer

(Redirected from Diamond Age)

Placeholder for The Diamond Age

!!Warning: Article contains spoilers.

Stephensonia

It's all about how YT lets Nell find her 'true' place.

Authored entries

- Stephenson:Neal:The Diamond Age:00:Let's Pretend, Alice, to Be an Artifex Conjuring a Working Primer Prototype( A.A )

- Stephenson:Neal:The Diamond Age:33:Common Economic Protocol...(Mike Lorrey)

- Stephenson:Neal:The Diamond Age:40:Protocol Enforcement...(Mike Lorrey)

- Stephenson:Neal:The Diamond Age:69:Dinosaur, Duck, Peter, and Purple ...(Alan Sinder)

- Stephenson:Neal:The Diamond Age:377:balkanized...(Alan Sinder)

- Stephenson:Neal:Snow Crash:14,41:_Franchise-Organized Quasi-National Entities_(Mike Lorrey)

Community entry:The Diamond Age, or A Young Lady's Illustrated Primer

Mostly from Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia.

!! STORY ELEMENTS REVEALED BELOW !!

The Diamond Age, or A Young Lady's Illustrated Primer is a cyberpunk or post-cyberpunk novel by Neal Stephenson dealing principally with the subject of class and cultural tribalism in a world where nanotechnology seems ubiquitous. Key features include:

- the contrast of neo-Victorian and Confucian views held by major power figures in this world, and the contrasting way they view the dangers and opportunities of molecular assemblers and artificial intelligence as applied to child-raising

- an introduction to encryption ideas in the form of a fairy-story suitable for children - this being the Young Lady's Illustrated Primer itself - which the reader encounters with the heroine as the novel unfolds

- a female-coming-of-age central plot, or bildungsroman, which focuses far more on adventure and far less on sitting around and discovering boys than the works of Judy Blume et al.

- a setting in which nation-states are obsolete (think of NYC's Chinatown sharing a government with Tokyo's Chinatown instead of with NYC's Little Italy and you've got it).

The Plot

The primary protagonist in the story is Nell, a street urchin who illicitly receives an -like interactive book (or "primer") originally intended for a well-bred child in a neo-Victorian tribe. The story follows Nell (and to a lesser degree, a few other children who receive similar books) as she uses the primer to overcome both her lack of education and her deficient parenting. Although Stephenson seems to be commenting superficially on the role of technology in child development, his deeper and darker themes explore the relative values and shortcomings between cultures.

The World

The world is divided into many phyles, also known as tribes. There are three Great Phyles; in alphabetical order, they are the Han (consisting of Han Chinese), the Neo-Victorians (consisting of Anglo-Saxons, including Indians and Africans who identify with the culture), and Nippon (consisting of Japanese). The novel deliberately makes it ambiguous whether Hindustan (consisting of Hindu Indians) is a fourth Great Phyle or an association of microphyles. In addition to these larger phyles, there are countless smaller phyles. Nanotechnology is omni-present, generally in the form of Matter Compilers and the products that come out of them. Exotic technology such as the chevaline (a mechanical horse light enough to be carried one-handed) and smart paper that can show you personalized news headlines are personal-use products, while major cities have immune systems made up of aerostatic defensive micromachines. Matter compilers receive raw materials from the Feed, a system analogous to the electrical grid of modern society. Rather than simple electricity, it carries molecules, and matter compilers assemble those molecules into whatever goods the compiler's user wishes. The Source, where the Feed's stream of matter originates, is controlled by the Victorian phyle, though smaller, independent Feeds are possible. The hierarchic nature of control the Feed represents and an alternative technology known as the Seed mirror the cultural conflict between East and West that is depicted in the book.

Shanghai

In a Shanghai transformed by the technology to create everything from food to buildings on a molecular level. Brilliant Nano-Engineer John Percival Hackworth is commissioned by an obscenely wealthy Neo-Victorian to create an interactive program in the form of a children's book for his granddaughter, hoping to teach her how to be an independent thinker. In the hopes of improving his own daughter's chances in the world, Hackworth pirates a copy of the book, but loses it to a gang of young thugs. In this manner, an extra copy of the Young Lady's Illustrated Primer ends up in the hands of Nell, a poor, young, tribeless 4 year old on the bottom rung of society. The Primer becomes her best, and often only companion, teaching her how to read, fight, and think for herself. One the other side of the Primer, propping up it's only flaw - convincing vocal software, is a "ractor" named Miranda, finding she is developing a strong maternal attachment to a child she knows only by reading between the lines she is fed, on contract, at her soundstage elsewhere in Shanghai.

Nell (and to a lesser degree, two other neo-Victorian girls who receive similar officially funded books) use the primer to overcome both her lack of education and her deficient parenting. Although Stephenson seems to be commenting superficially on the role of technology in child development, his deeper and darker themes explore the relative values and shortcomings between cultures. Eventually domestic violence causes Nell to flee her home, and lands her in Neo-Victorian society where she displays her adaptability. Hackworth becomes entangled between the Victorian government and the outlaw Chinese government that aided his attempt to copy the Primer for his daughter, finding himself forced to design a new wave of Primers for the government of the Celestial Kingdom, and sending him into a ambiguous quest as a double agent for Her Royal Majesty's Joint Forces that will see him lost under the delta of the Frasier River in Vancouver, British Columbia, for quite some time.

(The Diamond Age is most likely set in the same universe as Snow Crash, many years later, based on the assumption that Snow Crash's protagonist Y.T. reappears as the aged Miss Matheson who drops oblique references to her past as a hard-edged skateboarder. In a book signing at the Harvard Coop bookstore in Cambridge, Massachusetts on October 8, 2003, Stephenson affirmed the connection.)

Little Nell

Clearly not Chiseled Spam - heh

More bases for this assumption include: * Stephenson's short story "The Great Simoleon Caper" which refers to both the Metaverse seen in Snow Crash and the First Distributed Republic[1]seen in The Diamond Age. (speaking of short stories, another one which fits in the Diamond Age milieu and even shares a character is "Excerpt from the Third and Last Volume of Tribes of the Pacific Coast") * references to Franchise-Organized Quasi-National Entities (FOQNEs) in both novels.[2].

This book is probably the most cited example by those who disparage Stephenson's endings. These critics are dissatisfied with the ending because, after many pages of intensifying tension, the conclusion both fails to resolve all of the tension through explicit action of the protagonists and leaves some of the characters' eventual futures inconclusive.

It's not hard to see why they're dissatisfied, given that only the central plot of The Diamond Age is resolved while life goes on in the background (with the subplots unresolved) instead of everything grinding to a screeching halt at once (with "and then they lived happily ever after"). Moreover, some readers may even think Hackworth is the main character instead of Nell (because his subplot is so detailed and because the Dutch translation is titled The Alchemist) - which would make the way the ending ignores him to focus on Nell growing up especially confusing. Here's a breakdown of the three plots:

- "Coming of Age" plot

- begins after page 1 (Nell's not even born yet)

- ends before the last page (Nell grows up, leaves home to seek her fortune, endures a baptism of fire, and finds her place in the adult world)

- "Hacker vs. System" plot

- begins before page 1 (Hackworth's already discontent with his position in life)

- doesn't fully end (but Hackworth's not the main character)

- "Moral Kombat" plot

- begins centuries before page 1 (the tribes/faiths vs. each other, cities/city-states vs. nation-states, tech-haves vs. tech-have-nots, etc. clashing in 2100's Shanghai is nothing really new)

- stalemated at last page, thus realistic (these things never truly end but simply morph into new arrangements of conflict)

However, other critics laud this book's ending for Nell's transition from mere student to major sovereign and its consistent, if subtle, conclusion that those children who were raised with the original copies of the primer (which included technology which allowed oversight by caring adults) became fully-realized and independent individuals, while an army of children raised with modified clones of the primer (which were fully automated, and so lacked any "parental" oversight) became efficient, devoted, but inscrutable followers. Arguably, such an interpretation might reasonably follow from a single, dark allusion early in the book which suggests the cloned primers were intentionally disabled by the neo-Victorian engineer who designed them, maybe so as to foster a propensity for the abandoned Chinese infant girl children who used Doctor X's cloned Primers to follow the leadership of Nell who used her purloined copy, although this may not have been Stephenson's intention.

It is just as easy to interpret this as a desirable feature from the point of view of the Confucians, however, who emphasize duty, honesty and obedience in their training of women. A neo-Victorian officer might be useful and creative, but, in an army composed only of Confucians, would be quite disposable, and hardly pose any major threat to political leadership. The limits of the authority of officers, more than the degree of visible tactical control, is an emphasis of Confucianism.

At any rate, it's very hard to tell if the Mouse Army is merely efficient and devoted or also usefully creative. For all the reader knows, as one critic on Usenet noted, "whenever not busy rescuing Queen Nell they may well have been interesting people, stimulating conversationalists, and most excellent tea party guests." (Merritt)

The novel is also notable for a number of incidental descriptions of other cults or groups, such as the Reformed Distributed Republic, which in contrast to the elaborate cultures (or "phyles" as they are called) imposes a minimal civilization protocol that only tests the willingness of members to risk their lives, and come to each other's aid by following instructions, with little or no capacity to understand the importance of tasks they undertake in doing so, but a full understanding of the risks. The world of The Diamond Age is replete with "phyles"--communities organized around a cultural tradition, an ideology, a religion, a shared goal, or something else entirely. Ashanti walk down streets teeming with Boers, Senderos, members of the First Distributed Republic, Heartlanders, and "thetes," the occasional individuals who belong to no group. At the top of this heap sit the Neo-Victorians of New Atlantis and the Nipponese, with Hindustan jockeying for a position next to them. Stephenson has some ideas about culture in this book that he develops more fully in ''In the Beginning There Was the Command Line, which you can find in the Stacks section of this site. Let's just say that he's not a cultural relativist.[3]

War spills from China's interior into Shanghai, Nell's quest to the end of the Primer leads her to seek her unknown "Mother", that she has always sensed 'between the lines'. Hackworth seeks the meaning and identity of the elusive "Alchemist", a shadowy figure who blends information processing with the unconscious human mind. Critics miss why the Seed is better than the Feed.

The Real World

One term which was apparently coined in the novel, "Anglosphere", went on to be popularized by journalists as a useful term for understanding international relations. The Diamond Age won the 1996 Hugo Award for best novel.

An effort has been put forth to create a MediaGlyphic language as mentioned in The Diamond Age. The website: here

References

- Merritt, Ethan A."Re: The Diamond Age -- Honourable Failure" (9 May 1996)[4] ]

Related links

- Neal Stephenson

- Snow Crash

- YT

- Miranda

- PhyrePhox

- Phyle

- Mike Lorrey

- Mediaglyphs

- List of Characters

- List of gadgets and technology

External Links

- Religious Groups in Literature - "...could not come from any of the engineering works associated with major phyles--Nippon, New Atlantis, Hindustan, the First Distributed Republic being prime suspects...' "

- Defines FOQNES

- TDA:YLIP Review

- Google SF Group Thread on THE DIAMOND AGE

- Simoleans!

- cyberpunk

- post-cyberpunk

- nanotechnology

- neo-Victorian

- Confucian

- molecular assemblers

- artificial intelligence

- encryption

- Judy Blume

- child development

- Hugo Award

- In the Beginning There Was the Command Line